Interview with Ricardo Brey (CU, 1955), Ghent, July 7, 2020.

Let’s start in the atelier. So we are here in the middle of the atelier. How does your day start?In the morning you get up, you take a shower, and you come here. Do you know what you are going to make while you’re standing in the shower? Or is it when you come here and you start picking up things? Or do you see something hanging and you think “Okay, I will…”

No. I always leave something the day before. For instance, I know I need to glue this piece of paper now. I could do it, but it is better to leave it for tomorrow. So you don’t have to start from the cold.

Ah, the philosophy of not doing everything… Like writers do sometimes. They know what they have to do, but they stop just before finishing, so they know what to do the next day.

Yes. You are warming up. So you do not have to start from zero again. You are starting from, let’s say, ten. I think it is difficult to start from zero. Sometimes it happens, you finish the work and you finish the work the day before. But I rather prefer to finish the work the next day.

And if you say “It is finished.” What do you do? Do you sign it, for example?

No. I never sign it. I only sign things when they go out of the atelier.

So if it is hanging you can still change it. It is not finished until it is out of the atelier.

And with some drawings I like thinking that they are finished when they are framed. When they are protected from me, behind the glass.

Yes! That is what you did with the series Universe. It was also a sort of lockdown for half a year. You drew and drew, and you had more than a thousand drawings which you put into vitrines afterwards. And then you had something like “Now they are protected from me and from the outside world.”

Sort of the… there is always doubt. A kind of healthy doubt when the work is finished. You know, it is better to have this doubt until the last moment. It is healthy. To not say “This is definitely finished.” Sometimes it is very hard.

Yes. And sometimes a work is never finished. It is always surviving.

I remember once I was in Japan and the director of the museum that invited me had a beautiful piece by [Joseph] Beuys. It looked very spontaneous. But the director remembered that Beuys spent the whole day working on that. The action looks spontaneous, a sort of genius rapture that was taking over. But no! He was going to the garden and picking flowers… He told me they were watching him in secret. He was smelling leaves and making some lines and then erasing them. And I love that, because when you read the books, you don’t see this. This is so private that only the memory of someone who saw it can give you this insight into how things are. And I love that, because I know this feeling. In the end, it looks like the artist was taken over by madness and “Poof!”, but it is not like that. Well, sometimes you do go through this type of adrenaline. But sometimes it is more another way of working. The adrenaline is in the work, not in you.

Like a leaf! A leaf in the wind.

Like a leaf… but it doesn’t always happen like that. It doesn’t appear like that.

You like working with found objects. You like going to flea markets and then in your imagination you start to assemble. It is a story in your head on the one hand, I think, and on the other hand it is like when somebody is painting and they say “Ah, that colour or form is good.” The content and the form are simultaneous and in interaction. You do something spontaneously and you think “Oh, it can be this.”

I think it is a strategy that I took from being born in Cuba. Over there, nothing is waste, nothing is thrown away. Everything has a use. And that gives me a mental tool. Because here, there are a lot of things. Here, usually the associations go to the readymades of Duchamp, but the readymades of Duchamp are, may I say to you, a sort of step in the culture. It does not come from inside the culture. It is different if you are making a readymade in Africa, because there it goes from the inside to the outside. It is not something that is planted there. Duchamp planted that idea here in the culture. In a lot of places, may I say even more than half of the world, the things are not like that. There it comes from the inside, from a place of need, because you need it and you use it. And that is what I am trying to approach. Here I am filled… I am in luxury, because I can use everything.

So for you… You are aware that all the products are a luxury…

I like giving them a second chance.

And therefore you respect the things. When you create your three dimensional drawings, you are sort of creating a new world for us. And it is not always the most beautiful world. It is a bit… you like what you are making. It is also a tool for you, for checking reality with other eyes. You believe you can do this with the power of art, when you make things, when you assemble things. This is also the case with your expositions; they are not clean. You are really making a flowing world. It is all poetry. You want to give us something and you hope that when we leave the exposition we are in another world or at least think about the world.

I think… you pay a ticket to go to a museum. The visitor has already paid ten euros, so as an artist you need to be generous. You need to give something to the public or at least show them how you see reality, how you see art. You need to show what your experience with life is, the type of experience you have as a person. I like the Argentinian writer Julio Cortazar very much. He said something very beautiful in La vuelta al dia en ochenta mundos. He goes to a concert of Louis Armstrong, the jazz musician. And at the end of this beautiful description of what happens at the concert he says “Well now Louis Armstrong,” who was already very old at the time “Is in the hotel, taking off his tie, resting… But all of us have a little Louis Armstrong still playing the trumpet in our minds.” And for me that is so beautiful. The memory of what you do as an artist…Still playing, still painting, still doing something in the brain of everyone who looks at art. And that can be permanent.

You sometimes relate your art to music and rhythm. Music might have been your way, but you didn’t go down that road. You chose art. For Flanders, you unveil things we do not know, because you are coming from another cultural background, you bring new things. For instance you work with and reinterpret elements from traditional African art and from Western art. You don’t want to connect them in a cliché way, but you like it when they intertwine…

You know… What is pure Western culture? I don’t know. Because the Greeks were copying the Egyptians to make classical art. And you see with many of the things we call ‘pure Western culture’, the background comes from Asia. Sometimes we never know where they come from. That for me is very interesting. Because now there is this discussion of “this thing belongs to me.” But in the past, nobody cared about that. When they were building Alexandria, Byzantium or Athens, nobody was thinking like that. People were thinking in terms of cosmopolitanism. Cosmos. We are in the cosmos. Not “This belongs to me because I am Greek.” This idea of property in the culture is recent. It is about power and discrimination; it is about things that are now in the open. My last series of works is about the lack of belief in western civilization now. The temples are empty. These sculptures on the wall are imitations of gargoyles form the Gothic (titles: Rustic Vessel, 2019; Converse, 2018; Decoy, 2019; In Its Sleep, 2020). Because my new landscape for the last thirty years has been the Gothic. So there are pieces of the Baroque and of the gothic cathedral, but I put something extra there like that pair of shoes or that bird that is hanging there.

These works haven’t been exhibited yet?

Well, some of them have been exhibited already.

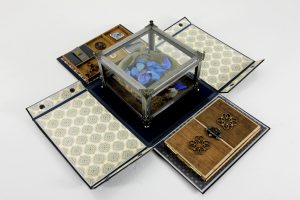

Before you made more individual ‘pieces’. Then you decided not to make less ‘pieces’, but to make larger series. Like, for example, Universeand now also the Boxes. Because you like… you want to protect your work. You like working in the smaller boxes, but it is also like, to protect the work a bit.

The Boxes came from what I was explaining to you in the beginning, when I was making all of these drawings for the Universe.There comes a moment, when you get to five hundred drawings, you need some place to put them and you need to count them. So I started to put them in boxes. And I started to enjoy counting them. One, two, three, four, five,… And this feeling of revelation and magic that happened, because I would forget some drawings. But I would see them again and say “Ah, this is beautiful!” And I realised, in medieval times people would not look at paintings as we see them now. Art was behind curtains or a closed door. There was this sort of discovery. Now everything is in the open, on the white wall. I think part of the magic is to open, the process of unveiling and discovering.

Yes. Things don’t go fast in those works. They go slowly, with respect. Like a ritual.

Yes, so I thought “That is a good idea.” It is quite simple. So that is when I started to make the Boxes. And I liked it, because this small idea started from, like in the medieval times, the microcosmos and went to the macrocosmos. It started to have this double situation. From small things to big things. So in time I started realizing that our head is a box. Our heart is in a box, we live in boxes and we finish our days in a box. Boxes are for protecting things that are very precious. Our heart is protected by this boxlike bone structure, because it is very precious. Our brain is protected by this perfect box, because it is so precious. So you start seeing that box metaphor everywhere. And the only thing you need is a way to deliver it. I found this beautiful expression by a neoplatonic writer who said “Psychological moments need something to contain them.” So I started to develop multiple me’s to make the Boxes. Extensions of momentums. Waiting to appeal to someone. It does not necessarily need to appeal to the same person. I multiply myself, because what we call ‘us’ is so multiple. It changes in time, it changes in situations so you can play with that. It is not about style as a painter, but it is about momentum that I try to catch.

And that you try so save. Your work also references nature, birds. It also knits together legends, stories and you try to materialise it. And you try to… it is also an energy that is in it that you…

There is this beautiful philosophy in Japan, which is the empathy towards objects. That is very difficult to talk about in the West. The West always wants to conquer and now with the cover-up of science, there is no empathy towards things. But in another part of the world there is another philosophy, there is another way of living. A kind of empathy. So you arrive at these things which are neglected there and you say “Wow, you are so beautiful. Let me do something for you. You can be art.” So you give them a second chance. You give the anonymous a chance to have a name. They become art. This is a map that completely changes how you make art. You respect the things. It isn’t making fun of things. They are here and they need to be respected. That goes for everything, for the natural world and for retrieved bicycle wheels.

You have also spoken about Taoism, about Sufism. That everything returns and is the same, but also not the same and that we can look at things with other eyes.

When you were a child you probably did the same. You see floor tiles and one is black and the other is white. And you would say to yourself “If you step on the black you are going to fall into a sinkhole.” And you believed it! You could feel the panic. The fear is real. Art does the same.

When you show your art, what kind of reply do you receive: “Hey, Ricardo, I liked it.”? When is your heart the warmest? After they say “It was interesting.” or after they say “It was beautiful! Or difficult, or hard”?

Well… You know… One of my best memories… Years after making the work of Documenta IX with Jan [Hoet], in 1992 I was in a restaurant with a friend and with an artist from Sweden that I had never met before. And we were talking. And I was introduced to this person, told him my name. Almost in the middle of our conversation with these two artists, I said I was the one that made that work, Untitled, in Documenta IX and he said: “I remember.”…What a compliment! Thirty years ago I made a work and this person said “I remember.” Nobody remembers anything anymore! People can forget something they saw yesterday.

Yes, and we have so much, here in Belgium. So much art.

In the whole world!

In the whole world you think?

Yes. It is everywhere.

It is different in regions where there is not so much art as here. I read that you said that here in Ghent you can concentrate on your art. Which wouldn’t be possible if you lived, for example, in New York. That you would always be in the streets, talking to people.

I mean… People… Art now is a thing to consume. It is not something you are supposed to remember. For me the most important thing when someone leaves an exhibition is that they remember it. For me the most important thing is that you remember something. This Swedish artist didn’t know my name. He didn’t recognise me. For him I was just somebody, but he did say “I remember the work.” That is the most important thing. Because so many people remember the name of the artist. They remember the name, but not the work. That is really sad. It is better to remember the work. I don’t know the name of the person who made the Venus of Milo, but I do remember it is a good work.

And do you have different key works for yourself? Or is it more that people say something about the work and someone else picks it up.

You deliver things, but you don’t decide which one people are going to choose. I like engaging with what they see. In the MKHA, I was interviewing people for one month so they could open the Boxes in front of the public. I didn’t want to open the Boxes myself. Other people had to open them. So I sat in front of volunteers and talked to them and asked, for example, “Why do you want to open the Box?” And we talked about whatever, not about art precisely. I left the conversation very open. At the end it wasn’t me opening the Boxes, it was the people who came voluntarily that opened them. It was a wonderful experience. In the beginning they would ask: “Ricardo, when the public asks us about the Boxes, what do we say?” and I would say: “Tell them whatever you want. I don’t have a recipe. Open the Box, listen and talk. The most important thing is to be open to talk.” And what happened was that the people started to talk. And I was very happy about it. I didn’t tell them “This Box is about this and only this.” I let them decide what they wanted to talk about. The Boxes were just an excuse to talk, to communicate.

An excuse to talk and to have a conversation.

And the people felt free. In the same way that I was very generous to let people touch my work, I was generous in letting people talk about what they want. Now in Germany, in the Gerhard Marcks Haus in Bremen, I did the same. I let them change the Boxes that were to be displayed three times. And people engaged in conversations. I received a beautiful email from the director of the museum, [Dr.] Arie [Hartog], in which he said that people immediately started to have conversations about what they were seeing. That for me is very important, because people go to a museum and they don’t have any discussions. Dialogue is important and necessary.

No, they don’t talk to each other. It becomes an individual act.

Talking becomes social engagement. It activates a point of view. It motivates people who are shy to speak. One of the volunteers in the MKHA at the beginning would say: “I am too shy, I don’t know what to say” and then she ended up being one of the best ones in the group.I told her that if she didn’t want to say anything that she didn’t have to, that she could just smile. One time I went to see one of the opening sessions in the MHKA. It was a discussion, a debate, it became a forum. A place for engaging in talking and meeting people.

That’s also what art is about. Not only to sell and hang in a museum, but also to open things, to break things up,…

It is part of the education. We are social animals.

But if you are in your atelier, it is a lonely job. You said somewhere that you need to be lonely to make art. That you need your space.

Yes, but lonely in that sense isn’t to be isolated from society.

No, not isolated… But if you make works like the 1004 drawings.

Then you need to have time.

Time to… for you it is important to have time and space…

Because I need to do it. I must do it. But not in the way that you become… it is to create a sensibility. To make sure art isn’t only seen as something you see over there that nobody is allowed to touch. And that nobody ever gets. That it is only for the top. You make art for the people.

But there are people who say: “I make art for myself.” Do you think of ‘the other’ when you make your works?

I make my art for myself, but that doesn’t mean I don’t want to show it to anybody. If you say: “I make my art for myself.” Then why are you going to the gallery? Why are you so protective of your fame and your name, if you make your art for yourself? It is just pretending. That is fake. It is a mask.

And can you live with that? Because we do live in Belgium and that is a reality. Don’t you break masks sometimes?

I have been here for thirty years and I haven’t changed my point of view. I have enough living with myself. I don’t need to educate anybody. Everyone knows what kind of game they are playing and so do I.

And do you play the game?

I don’t play any games. I am who I am.

And if they play games with your work?

Then they are wasting their time. They are cheating. And they know they are cheating. I am not stupid. I can’t be stupid because I’m a black guy living in a white world. I can’t be stupid. I have to keep my dignity.

You are lucky, because you are very respected for what you do. Some people have less luck, because they do things that are not accepted.

I had times where my work wasn’t accepted. In my country people didn’t accept my work.

Was that when you studied at San Alejandro in Cuba? Because after that, you went to New York and met Jimmie Durham. Soon after that you were invited by Jan Hoet for the exhibition Ponton Temse and later Documenta IX. After that you stayed in Ghent and made many large museum expo’s in places such as MKHA and SMAK. You were also awarded prizes such as the Prize of the Flemish Ministry of Culture and a Guggenheim Fellowship for installation Art and Sculpture. And in 2015 you participated in the Venice Biennale All the World’s Futures. I must imagine it felt good that with your own personality, your own vision, you can make so many things happen.

And I’m not finished yet! I’m just warming up.

But this year you turn 65. You can retire like Panamarenko.

I mean… All the time, art has this duality. We are not bad guys, we are just struggling with the duality of many things. Probably the curator has something similar. We know what is right. We can… but to arrive at the right things is very hard. Because things are not meant to make our trip easy. And sometimes you have this dream that isn’t very clear to you but you know that you want to achieve it. You know that you want to make these exhibitions but it is hard to accommodate all the ideas into that project. The duality lives in us. We know that we can do that. I am a good painter. I could cheat by painting, because I studied painting. That is why I never go to exhibitions of painting. You know why? Because I can smell when people are painting for money. And they want to put candy in your mouth and they say “Please buy me. Because I put this yellow here for you, my sweet sweet collector.” I can do that, but I won’t.

To struggle with small things and not to… It would have been easier for you to just paint or draw. I mean, it is just one folder and off it goes.

That is the reason why I count how many good painters I have seen in my whole life of which I can say: “Wow.” It’s only a handful. When I see one, I don’t restrict how emotional I can be. I know they are good painters. You can feel your heart beating. You feel happy. I don’t feel jealous, I feel happy.

And that is what you want when people see your work. You want them to be happy, to feel their hearts beating. Or when they see an exhibition, you also work in the space.

You know, in the end, when you make art, you are a happy person. Even with the struggle. And maybe… today wasn’t a good day. You didn’t make anything good. But then you just have to say: “Tomorrow, I will do better.”

But when you go inside of the kitchen. When do you say to your daughter: “Okay, I made a good piece today.” Or, if it didn’t work that day, do you go into the kitchen angry?

No.

You feel it when you’ve had a good day? Because sometimes when you make art, there are days that make you feel deflated.

The thing is you need to live with that. You need to know how you can handle that yourself.

You always say: “Tomorrow is a better day.”

Yes. You think: “Okay, today is not my day.” So I clean the floor. And I clean my workspace. Or I go to the streets and walk.

Ah, so if you say: “Hmm, I have no spirit today,” you say: “Hopla!” and go outside.

No, no, I am here. I am cleaning the floor. It used to be painting the walls. And I wash the dishes every day, because that gives you some sort of discipline. I wash the dishes, I feed the birds outside, I read my books, I listen to my music and I remember that there is always going to be a better time than today. The things that aren’t good are the things that escape from my hands.

If you make a work that doesn’t feel like yourself, do you destroy it?

You are never going to see it. I would never show it. I don’t let people see what is not 100% me.

Because sometimes you make art when you are not a 100% with yourself…

I made some drawings, most of it happens with drawings…

Yes, that is different. That is another way of thinking then.

Yes, you need to think and say: “Maybe not today.” I have drawers full of unfinished drawings. They are from five to ten years old. Sometimes they are just missing a single line. But on that day I just do not have the communication to draw that line. And one day I will rediscover that drawing and finish it and I am happy. I have learned this with age. When you’re young, you want to finish everything in a day and you destroy a lot of potentially good things, because you’re in a hurry. You are in the middle of the fire and you burn things. And now I find drawings and I finish them. And there are things that I make now of which I know that they are almost there, but that they aren’t a 100% there yet for me. They aren’t 100% alive.

But if your daughter arrives and says: “I don’t like this”, will you listen?

You know, I sometimes call her snake-tongue. She has a very good eye. So I listen to what she has to say. She also provides me with new music, which for me is very important.The music she provides me goes to my work. There is some kind of young blood in the sounds. Because I still listen to the music I listened to when I was younger, but having a young daughter gives me new artists. I listen to musicians I wouldn’t have listened to, because I am 65. With new music, I can discover new ways of working. A new metaphor, a new image. It activates new things for me.

Yes, the work you make feels very contemporary, but at the same time also very timeless. Because of the predominantly brown and the black tonalities. You can’t tell if it is recent or it’s made fifty years ago. But you also say: “Time doesn’t matter to me if a work was made yesterday or thirty years ago”, because you have artists who say the latest work is the best work.I don’t agree with that.

No. I like my work. I sometimes see work from years ago and I realize I could do it better now, but I accept that it has already been done. For example, the idea of the Universe started from scratch. At that moment, I didn’t have money, just these little papers and even when I had a big atelier I still worked at a small table. I started to read a lot of scientific books about evolution, because the work needed to have a backbone, a spine. Now that I have accumulated all this knowledge, I can’t repeat the Universe again. I cannot do it, it is already done. It is quite dramatic. In the moment you’re ready to do it you have already used all that knowledge and those solutions. You cannot make another building. That’s it. It is already in that project. It is quite frustrating in a way. When you are ready to deliver, it is already finished. It is like building an exhibition. How beautiful is it to build an exhibition? You have conversations, discussions. Every night you are tired… you arrive the day of the opening and it is just two hours of saying hello. And then the lights go off. You aren’t there to know what people think and you are frustrated, in a way. But you delivered something, you have given something.

Sometimes going to your own expos feels like seeing someone else’s work. It is good that you can see the work yourself and feel it is strong work.

You need to be critical. You need to check your ego everyday. You need to check it, because that is very healthy. Not let the infatuation take over. You need to have an ego to do the work. You need to have this confidence. It can give you power. But you can’t become a slave of this power. The moment you become a slave to this power you stop listening, you stop seeing. You become completely disconnected. It is what happens to politicians. You become a politician! You become addicted to power. No longer an artist.

But it is difficult. Because with Adrift for example, it has gone to Sittard, New York, Bremen. But for you it is difficult to work with museum directors because you have to constantly say: “Yes, yes.”

No, no. I never say: “Yes, yes.” We always talk. You don’t have to think you are the smartest guy at the table. You need to be smart and listen to what other people have to say. The show in Bremen was different from the show in Sittard. Because in Sittard, I wanted to show only the photographic works, whereas in Bremen I wanted to show 3D works and the Boxes, because the museum looked like a house. The collaboration with the director in Bremen was fantastic. At the end we only had the big room left to install. I had planned four tables and the director said “Why don’t you put them together and make two large ones.” I thought it was a terrible idea, but I tried it out and in the end it was the best idea. That’s the moment that you control your ego and admit. I said: “Now the show is finished” and the space immediately took another dimension. It is like in the orchestra. You need to listen to the others. The first thing I do when I’m working on a show is to tell my assistants to tell me if they have a better idea than me. And sometimes I have assistants that suggest to me: “Move this to the left or to the right.” and we do it. I am smart, by listening. In New York there was a discussion about the height of one work. And we asked the two technicians where we should hang it. One of them thought it should go lower and the other said it should go higher. They were the ones that figured it out. It wasn’t my idea. They had the power to decide and they used it wisely. They care about the work. You can’t become blinded by your ego and say: “This is mine and this is the only way you can do this.”

Yes, but many artists think that way.

Poor them. They lose so much.

The Boxes are also a way to structure your mind. You have so many drawings and paintings. The Boxes are a way to construct the world.

Yes. In the presentation in Bremen there were different rows of Boxes on the wall. The bottom ones you could see into, the second row a bit less and the top rows not at all. It is a bit like memory. The Boxes are memories. The farther away the memory the less you see. Boxes sometimes work as a building, sometimes as storage, sometimes as a construction. What I like is that when you see the work, you are destroying the work. The Boxes always have the same measurements. So there is always a dilemma of how you will or can fill this space. The dimensions are always the same, but the solution isn’t. It can’t always be the same. So it is quite intriguing for me. And now it is quite interesting as well. With the pandemicI kept asking myself: “What can I do?” and I said: “I am going to make some new Boxes.”

It is like making a frame.

All these blue drawings I have made lately are all because of the pandemic. Blue is the colour of this planet. This planet is blue. Blue is the colour of the infinite. Now, we are all claustrophobic because of the lockdown. The blue is the sea, the blue is the sky. So what is the colour of space? Blue. I started to make blue drawings. Because it appeals so much to the melancholy and to the inner vision. And to our planet. Mars is red, the moon is white, but our planet is blue. So I said: “Let me do some drawings in blue.” It seemed okay to me now that everyone is feeling confined, to remember that outside there is space, the ocean, the sky.

In an interview you said that you hope there is paper in the next life. That if there isn’t, it would be hell.

That was a joke. I hope there is enough paper and pencils there. But just in case I will continue to make things now.

Your work also works with coincidence, but is there also humour in your work?

Yes. Sort of.

Yes? If we look at it or just for yourself? Or is it while you are working that you begin to laugh?

I find those tennis shoes there. If you feel like you look at them and you know something about it. A sort of complicity.This type of spontaneous gesture.

Or sometimes the way you find things is funny, like the gloves you collected. It is a sort of ‘funny small thing in life’ to look at it.

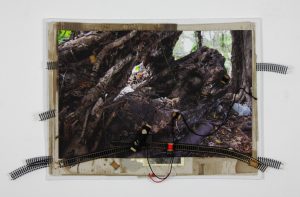

It is not a big laugh, but it is a small humour about it and sometimes it is a type of sad, melancholy humour. Chaplin has this type of humour. Sometimes you see the end of the film City Lights and it is quite melancholic and sad, but also quite funny when he says: “Yes.” with the flower in his hand. You can’t stop laughing and at same time can’t help feeling sad, or not feel the humanity there. And I like that. I grew up watching those films. When I hung this work in Bremen, the one with the bird, I hung it close to a window. And this window was full with the actual living birds. The real ones. And sometimes there was a split second of confusion where it looked like there was one inside. I didn’t make the work thinking about that, but when I arrived I immediately hung the work there and that happened. And that gives a type of humour about the artificiality of the space of about outside/ inside. So things which you decide at the moment, but that can give a lasting impression to the person who sees it. Like, to me it happened. The work is there, the bird is there, haha. And you smile. It is not that you have a plan.

So you always let it…

You need to know three of the walls. The fourth one is open to let these kinds of things happen.

Do you feel sad when works come back from exhibitions? When things come back from a gallery… is it difficult after something large to restart in the atelier.

No. I always leave something. The same as with everyday work. You need to leave something. Because you know, depression is very easy to catch. It is like the flu: it is very easy to become depressed. If you go to one exhibition and you don’t leave something in your atelier that while you are there you are still thinking of and mentally working on… it is like a welcome. You come back and you think: “Home.” And it feels good, because in long distance you were in the atelier working. For instance: tomorrow we need to go to Germany for an exhibition. I will leave something here. For one month we will be working there, but I will also be working on a drawing I have left here. It stays in my mind. And there, mentally, I make twenty drawings. When I travel I always bring things back. I go to flea markets or I go and buy new materials, or I walk the streets looking for objects. I am in this state of awareness. I was talking to Jimmie [Durham]: “Oh, Jimmie. The last time I went to New York… I just wanted to come back with a plane full of stuff. There is so much art on the streets” and Jimmie said: “Yes, it is my dream to walk around with two strong guys who will carry it all for me.” You are walking and you are working. You are not only an artist when you are in the atelier. You are working the twenty four hours of the day. This is a job that consumes the whole of your life.

So you work from seven ‘til six o’clock?

Yes. From seven until six.

Wow. And your work is finished in the evening?

In the evening it is finished. Yes. I need to have a family life. Of course I need to jump here to take the works by surprise: “What happened here?” And I move some things around and then leave them for the next day. And the first thing I do in the morning, before coffee, is to come to the studio.

Ah, it is like warming up. Like a jogger.

Because at that moment you don’t have a pre-judgement. Before, I used to put all my drawings around my bed. That was a long time ago. The first thing I did in the morning was look at my drawings. And I would choose: “You, out. You, into the garbage. You, you can stay.” But there you need to be… you need to feel that what you make is good. We are producing a lot of waste, and polluting a lot and sometimes art too is pollution. And sometimes I say to my wife and daughter: “Ah, you’re going out?” and when they are gone I start to open drawers and rip drawings up. Because the first jury is me. And when they come back they find a massacre. My daughter has ‘stolen’ a lot of my discarded drawings, she has kept pieces of them. But I have to do it. You have to make space for new ones.

Yes, space is important…

Mentally and physically, you create new space for everything.

It is always the… to stay in a no man’s land. That you have a part of your mind which is empty, which can jump to new thoughts, that is not worked to death.

Part of you always needs to be in a state of fluidity. In the Tao philosophy in China, the strongest is not the stone or the fire. The strongest element is the water, because water goes everywhere. It is fluid, it is permanent. It can open stones, carve them. Corrupts iron. Can put out fire. Water is a strong element. Your mind needs to be like water. Fluid, transparent, in rest, but always with this power, which is inside of the nature of the water. It is not like the fire. The fire is vitality, it is movement. The water is not. The water can be resting, can be like a lake. Or can be like an ocean, like a tsunami. It always has this power. Water finds a way. And that is how the brain has to work, with this kind of centralised power and at the same time with this type of rest. Like that the brain can find a way.

But if you have… and what if tomorrow ,you don’t have any exhibitions anymore?

I have already had years where I don’t have a single exhibition.

And you will continue?

Yes. It is not about making exhibitions. It is to spit out the demons. It’s to… I don’t have anything else to do. I just make art. I do it first for myself and after I do it for the people who like it. Some years I don’t have an exhibition. Of course it bothers me, but you try to have positive thoughts.

The interaction, the feedback,… it’s all part of the process.

People who know me say I have this very uncaring character… The Marx brothers, those funny guys. The one with the moustache and the cigar, Groucho. He is in a restaurant and he says to the waiter: “Keep the change.” and gives the waiter the money. The waiter says “Thank you!” and looks “But there is no change.” and Groucho says: “Don’t worry! Keep it anyway.” So for me that is the philosophy. Keep the change… It is who I am and it is what I can do. Sometimes you don’t have exhibitions. It doesn’t have anything to do with the quality of your work. If you are convinced and your loved ones are convinced, then you can live in peace with yourself. There is always going to be somebody who has more money than you, or whose name appears in the newspaper more often than yours… You can’t be in competition. You need to be happy. You can’t wait for a future in which you have a better reputation, because you may die and that ends up never happening. How many artists have died who never had any recognition? Some of them are the most beautiful artists! Look at Rembrandt, look at Van Gogh, look at Thelonious Monk! To me they are some of the best artists. I went to Miami Basel five years ago. I don’t like art fairs, it is art as merchandise. There were all these big names, good and bad. But there was something that immediately caught my eye. He was an outsider artist from the thirties. He made all his drawings in a notebook. He died in a mental hospital. Such beautiful drawings. I wanted to buy all of them. I immediately started to cry like a baby. And nobody cared about this work! It was so stupid of me, that I didn’t write down the name of the person who made them. But for me they were the best of the best of the best. That was good, that was art. It was the same feeling as seeing an image of the Altamira cave. Something that stays in your memory, bothering you.

And that is what art is about. You also took a risk. You came to Ghent after Documenta IX , there was nothing anymore. You could have decided to go somewhere else.

Jan [Hoet] said: “Stay here.” He believed I had potential. He said: “Stay here. I will pay for everything.”

But it is also a gamble to do it and to make art. You were already with your wife then?

Yes. It was a gamble for all of us.

It is amazing that you did it. You were two people coming to a strange country, putting your faith into one person. Some people get those chances but end up not taking them. And you took it with two hands.

Jan was the one taking a chance. I was thinking about going back to Cuba and he said: “No. don’t do that. Stay here for a while.”

Yes, that was something Jan could do. He took risks in his life and in his work.

He had a vision of what artists had to be. We didn’t have an easy relationship. We had a difficult relationship. I had to have this kind of gratitude towards him, but at the same time I needed my freedom. We didn’t talk for some years, but we understood that fundamentally things would never change. He believed that I could deliver something that was important. He pushed me to do it and in the end he understood why it took me so long to develop what I wanted to do. Because it is very easy for me to play the victim and I never played the victim. “I am black. You need to give me something, because I come from a third world country.” No. I am making the art of the future. I felt that I had to produce art for everybody and not make a prejudgement about who is going to see it. The same way I look at art: I see art without knowing who made it. A woman, a man, black, white, gay, straight,… I want to see what they deliver. I like, for instance, in England they have this big salon where they hang the works without the names.You are not looking like: “Ah, this is Damien Hirst, it must be good!” You are looking at the pieces. Like with that outsider artist from Basel. I saw his universe. That to me is the most important. I am happy to live here. This is a country that has a long tradition of art. Belgian people love to complain about everything and they forget how good they have it here. I like the silence of this country.

Yes! We are here next to a busy road and you don’t hear anything!

The first time that I was working here… I used to live somewhere else where the atelier was next to a pigeon breeder, so there were always pigeons fighting on my roof. There were also two hospitals close, so there was always a lot of noise. And then we moved here. The first time I was here alone, Paula and Isabel had gone to the movies, I thought the world had ended. It was so quiet that I said: “Oh no! Something has happened!” So I went to the street and didn’t see any cars or bicycles and thought: “It’s the apocalypse!” So I called Isabel. She answered the phone: “What happened? I’m at the movies!” I asked: “Are you okay? Did something happen? There is no one in the street,” and she said: “No, nothing has happened. Are you okay?” And then I saw a bike pass and everything was okay again. I appreciate this silence.

Yes, you really need that kind of quiet to work.

Before I came here, I had never seen blue flowers. I think they are fantastic. Where I am from the flowers were always pink, red, yellow, but never blue! I am not nostalgic. I miss my friends, but you always miss your friends. And your friends miss you.

And you go back every year?

No. I went back to Cuba in 2013 after twenty years without going. And went back because my mother in law was ill. But I am not nostalgic. Also my friends don’t live there. They all live in Miami. I also went back to Cuba for an exhibition, together with almost fifteen friends from here. Guillaume [Bijl], Ulli [Lindmayr], Femke [Vandenbosch], Dirk [Pauwels], Luc and Barbra [Darras], Koen [Van den Broek]… and we had a wonderful time. Because I was able to show them my country. And showed them places they would not have been able to see. After that I came back, and that was that. I paid my debt to my people. I showed them the type of art I was making. They gave me the whole museum. I saw the few friends and family members who were still there and spent time with Paula.

And all the artists from there, they didn’t stay there?

No, no. They live in Miami. The only one who doesn’t live in Miami is me.

Because in Cuba there is also a contemporary art scene, right?

Yes, there is a new generation.

But they have more Western influences, or the academies are freer than in your time?

The things are so different now… It is a new generation, a new way of thinking, a new reality about the Cuban revolution… I grew up with the Cuban revolution. I am the first or second generation of artists that was raised with the revolution. Totally different!

And the people who left for Miami did they have good luck?

Miami is different. Miami is a ghetto. You can live there without speaking English. It has a huge Cuban population. All my friends moved there together. Just a few live in Mexico and then me in Europe.

The friends you mentioned are artists…

Yes, most of them. They are the type of friends you can’t see for years and then see them again and talk like nothing has happened. Here I also have many good friends who I trust.

And can you also count on them to ask you things about your art?

When I started making the Boxes nobody knew what I was doing. They look like boxes, so nobody saw art… they saw boxes! So I started to call friends and said: “I want to show you what I am doing.” In the beginning, and still now, I had a lot of doubts about how to present the Boxes. For instance Luc [Derycke] and I said: “Luc, I don’t have a plan… because it can be performative, it can be a performance. Or it can be frozen. The Box is open when you arrive.” So you listen to what your friends have to say and start listening to their different points of view. And discussions and like that… It is a… Nevertheless you are here in the atelier. You work. Sometimes you invite people over for dinner and you show what you have been working on and they talk and you listen. They can be open to you to say anything.

It is nice to talk to you. I saw in other interviews that you have this entire philosophy. About life, about art, about the world, about everything. And you say things which are very beautiful. I talk to a lot of artists and it is not always like that. Art is not therapy, but you have to do it. It is a way of living.

Can you imagine at 65 coming here every day and playing with dust and paper… You need to be convinced about what you are doing. That it is worth doing every day. If you are building tools or machines, you know the function, the goal of why you are doing that. When you are making art you do not know that.

It is not useful. Are there days you feel like you would be better off working as a nurse in a hospital?

Those are my hero’s. Especially now. I see people who volunteer and go to the hospital and help people. What humanity! When you see so many stupid people, such selfish people… and then you see people who are doing the right thing without reward. In all the movies about the future people are killing each other, but now the future has caught up to us and what you see is a lot of solidarity. You need to trust people. They don’t do it for the money or for the prizes, they do it because they feel it is necessary. That is beautiful. That gives you a good feeling about life.

You also must be strong to come here, because it is not being self-centered. At first it was playing and then it became more and more serious. You must also become convinced that you are doing a good job.

You know, on the last day of the Universe exhibition in SMAK, we were behind the museum at the playground with Paula. I was a little bit sad. I had a wonderful time making that show and with the people at the museum and how people reacted to the work. I was almost melancholic. Suddenly, a father and his daughter passed by. They were carrying the book of the Universe. And they were looking at it and talking and looking and talking and looking and talking. And I saw their faces and they looked so happy. That healed my soul. For one moment my ego jumped out and I wanted to say: “Do you want me to sign the book?”, but they healed me and that was more important: What they gave to me without knowing. They gave me the feeling that what I do has meaning. I imagined them going home and unwrapping the book and them turning the pages. The book will grow old in this house. Immediately I felt happy. I felt full of energy. I feel that all the good things can be here. I can do that. And I am still here. And I am okay. They didn’t know, they didn’t need to know.

I can imagine it is quite melancholic. It is like coming back from summer camp: you are surrounded by people and movement and suddenly you are alone and quiet.

I am an extremely lucky person. One day I was in the tram and I was feeling very down. But really down, down, down. Suddenly a guy touched my shoulder. He was very young and he was shaking. He asked: “Are you Ricardo Brey?” and I said: “Yes.” and he told me: “We love what you are doing.” He then turned away and left. I didn’t have time to say anything. I felt very blessed in that moment. “We love what you are doing.” I didn’t get to say thank you. But I am very grateful for that moment.

《 Image 21: Universe, Installation view in the SMAK, Gent, 7 October 2006 – 7January 2007 》

HVC: And I am grateful for “our moment” here in your studio Ricardo, together with your daughter Paula.

All works are Courtesy of the Artist and Alexander Gray Associates, New York .

All images © 2020 Ricardo Brey/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

https://www.alexandergray.com/

http://www.ricardobrey.com/

– –

Photos: 1,22. Hilde Van Canneyt

Photos : 2,3,4,5,6,9,14,16 .We Document Art, Antwerp

Photos : 11,18, 21 . Dirk Pauwels,Gent

Photos : 7,8,10,13,17,20 Studio Ricardo Brey

Photo : 12 Christine Clinckx,M HKA, Antwerp

Photo : 15 Jens Weyers, Bremen

Photo : 19 Dan Bradica, New York